Compiled by London swaminathan

Date: 14 December 2016

Time uploaded in London:- 16-39

Post No.3449

Pictures are taken from different sources; thanks.

contact; swami_48@yahoo.com

The house of Mr Raman lies in the centre of a village called Puduppatti. Its walls are built of sunburnt bricks and clay, and its roof covered with palm leaves. It has got two outer pials facing the street, one on each side of the entrance. Immediately on entering we find an open hall , which is known as Koodam. In this hall male visitors are received, and the inmates of the house meet and chat together in leisure hours. It is also used a s abed room for the elderly members of the family. After an open space of about fifty feet in circumference we come to the house proper, which faces the north, and has a large hall, a store room and a kitchen. The hall is used both as a dining and sleeping room, and there is seldom any furniture to be seen in it, save a common village cot in one corner, pillows rolled up and kept in another corner.

In the store room are the provisions of living preserved in earthen vessels, and the clothes and other valuables of the inmates. In the kitchen are various earthen vessels needful for coking, and the brass pots and vessels which are used for eating and drinking. Near the kitchen there is a door way which leads into the backyard. This is used as a kitchen garden, and has in it drum stick trees, peas, greens, pumpkins, cucumbers, onions etc.

On the eastern side of the house a cattle-shed is placed, and in it this the cows, bullocks and buffaloes are sheltered. All these buildings are encircled with mud walls, in which there is only one opening, and this is available for both man and beast. The apartments kept for the use of inmates receive the light and air only through the doors as there is not a single window in the entire building. There is however, quite sufficient provision for free ventilation through the bottom of the roof.

The inmates of the house get up very early in the morning. The male members of the family go for their morning ablutions, and while they are away the female members sprinkle cow dung over the outer and inner yards, and occupy themselves in sweeping the house, clearing the cooking and eating vessels. They draw Kolams (Rangoli) at the entrance with flour.

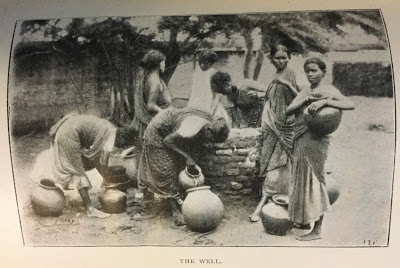

In their turn they then march to the watering places, where they bathe themselves, and wash their clothes, and bring water home for family use. The morning bathing is not , however universal among all the classes of the village community. While at the watering place they exchange lot of information with others.

In the house of Raman there are two females, Raman’s wife and his mother. When they have returned from the watering place, they attend to the work of feeding the men, and preparing for the lunch time meal. About 8 o’clock in the morning Raman and his brothers come in for their morning meal, which is generally some cold rice soaked in water the previous night, with butter milk and some pickle or chutney or some cold sauce. Having taken their morning meal, the superiors in the house leave in order to attend to the cultivation of the land or other works. As soon as the men have finished their meal female members help themselves to what is left of the dishes.

In taking their meals they all use the floor as their table, plantain leaves or brass vessels as their plates and their hands as spoons.

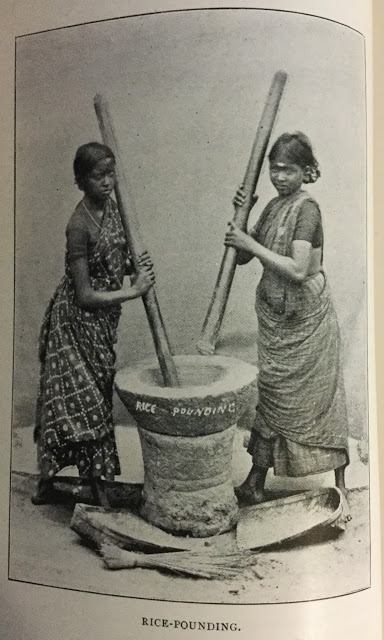

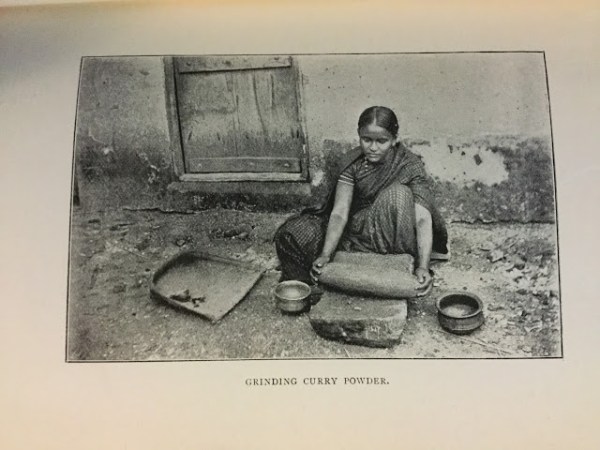

Following the female members in their daily routine, we find them busily engaged in pounding the rice and grinding the curry stuff, and dressing a few vegetables and greens in preparation for the lunch. Between twelve and one o’ clock the men return home hungry, and then there is placed before them a sufficient quantity of cooked rice, with some vegetable sauce, greens pulse – not to mention the attendant butter milk or curd/yogurt. The cooked food items are served very hot. The men cheerfully partake of this simple village meal, and then go to the outer hall and chew betel nut. Most of the times they sit on floor mats.

Then the females take their noontide meal; after which they rest for an hour, or even two, and during this time the men and the women converse together on common topics of the village. At about four o’ clock the female portion begin to occupy themselves with preparation for their evening meal, and in arranging the household things. At six o’clock Raman’s wife places a light in a hole, which is prepared for the purpose in the wall, and then prostates herself before the lamp, and smears a small quantity of ashes or kumkum on her forehead. The other members of the hose on first seeing the lamp do the same. Hurricane lamps and other portable lamps are used in different parts of the house.

About eight o’clock men take their supper, which usually consists of some pepper water (Rasam), rice and vegetables, and the remainder of the sauce that was prepared for the mid-day meal. Some people prefer light food like Uppuma, Idli or Dosa in the night. The female members follow the men in taking their supper, and all the eating for the day is over by nine o’clock and then they all retire to bed.

One day’s life of Raman and his family is a picture of all, for only slight differences are made even on festival days.

It is common among the women of the village to make their own fuel by making cow dung cakes. They use it in the fire place or mud ovens along with some fuel wood. Some are also engaged in in their leisure hours at the country spinning machine. Sometimes they go to the fields, and assist at the work which is being done by the labourers.

It is a very common thing to find uncomfortable relations prevailing among the village mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law. Perhaps ten out of hundred only have good relations and peace at home. Sometimes they may even be seen fighting like beats of the filed using vulgar village language, holding in their hands each other’s hair. Still, it must be understood they are not to be regarded as enemies until their death Today they fight one another, tomorrow they laugh together. One day’s fighting does not destroy another day’s peace.

observing the varied duties of and claims of our friend Raman, we cannot fail to admire the laborious spirit of this village cultivator. He is busy with many things. He has the care of his family, as he is the head of his house; and he has to direct his farm laborers and his brothers in attending to the work of the field. He must answer to the different calls of the village officers. He is invited to a wedding or to a funeral in his own village or to some distant village where he has relatives or friends. On some of these joyful or sorrowful occasions he takes his wife with him. Sometimes, if he is ill or otherwise engaged, he sends his wife or mother with one of his brothers to represent his family. There are many calls on Raman’s poor purse. The priest, the beggars, the poets, the pious, the guests, the village policemen, the medicine men, the weddings, the funerals of his relatives — all of them have a share in Raman’s earnings. For all the transport between villages they use bullock carts. They are always kept ready for any emergency.

Source: Indian Village Folk by T B Pandian, Year 1897,London

–Subham–

You must be logged in to post a comment.